The Tony Industrial Complex

I was having breakfast at Friedman’s on 47th, with someone in the industry I deeply admire, when, between bites of our meal, they suggested I look into Tony Award voting patterns. Specifically: whether shows with more producers tend to win. “The findings might surprise you,” they said, in that tone people use when they already know the answer and want to watch you discover it.

I was skeptical. Also intrigued. Also, if I’m being honest, immediately fantasizing about writing the exposé that would reveal the Tony Awards as this elaborate fraud. TONYS = BULLSHIT, the headline would read. I would become the Ronan Farrow of theatrical awards corruption. Lin-Manuel Miranda would block me on Instagram… it would be worth it.

Reader, the data does not conclusively prove that the Tony Awards are bullshit. And the truth, as I discovered over several days of regression analysis, turns out to be stranger and more conditional than any headline could capture.

How I Ended Up Running Regressions at 1 AM While My Sister Talked About Football

Right now, it’s Thanksgiving break. As all law students approaching finals know, that’s code for “the next three weeks of my life are going to be absolutely miserable.” I have a paper due on secondary liability frameworks for generative AI. I need to understand how Loper Bright impacts standards for analyzing agency action. These are sentences that, if you don’t go to law school, sound like I’m having a stroke.

I needed a break. Something to feel alive again.

My sister is home from Ohio State. We smoked a joint together on our back porch while our parents slept. She told me, with the fervor of someone who has explained this many times before, why this was finally the year Ohio State would beat Michigan. Then she transitioned, as she always does, into stories from college. Boys. Beer. Bad grades. The recurring themes of her semester.

I nodded. I made affirming sounds. I was not listening to a single word.

What I’m actually thinking about is how to structure a dataset of all Broadway productions since 2010, how to run logistic regressions on Tony win probability, and whether Claude Code can help me generate the analysis faster than I could do it myself. The answer to the last question is yes, embarrassingly yes, and this is either the future of knowledge work or the end of human intellectual dignity. Probably both.

At 1 AM, a little excited, very high, and with the particular exhaustion of avoiding administrative law, I started running the analysis.1

My parents would wake up in a few hours to start Thanksgiving prep. I would pretend I had been sleeping. This is not how normal people spend their holidays, but alas.

The Headline Finding (Or So I Thought)

By Thanksgiving afternoon, while my mom was in the kitchen engaged in her annual labor and my dad was watching some random YouTube video on Bulgarian desserts, I had a complete dataset and a working model.

I ran the simplest version first. Tony win as a function of producer count. Nothing else. Just: Do shows with more producers win more often?

The answer came back yes. Shows with more producers are more likely to win a Tony Award

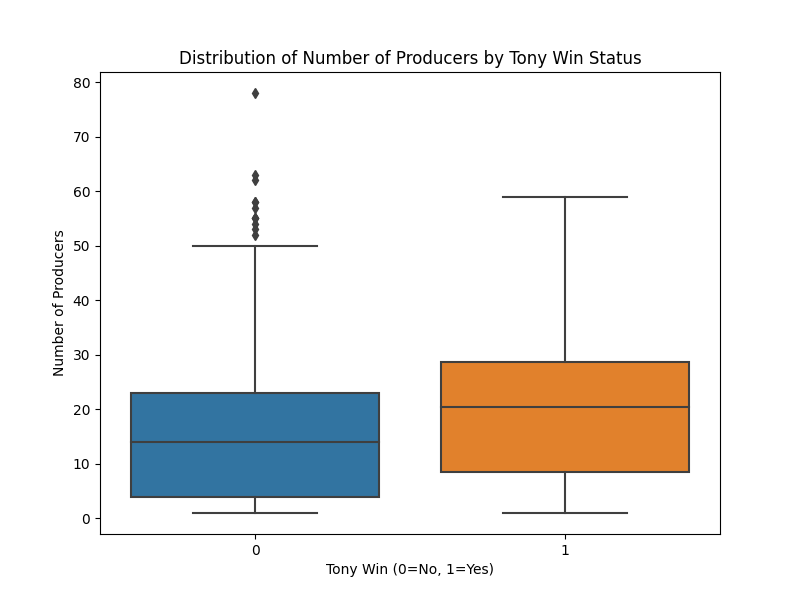

Winners averaged 20.6 producers. Non-winners averaged 15.1. That’s a gap of about five names above the title. A statistical test confirms this is unlikely to be random noise (p = 0.021, for those of you who find that sort of thing reassuring).

When I ran logistic regressions, each additional producer raised a show’s predicted win probability by about 0.26%. Go from ten producers to thirty producers, your odds tick up by roughly 4%. Not transformative. But real.

Look at this boxplot. The median for winners sits higher than non-winners, sure. But what’s interesting is the right tail. Winners stretch toward sixty producers. Non-winners cluster below fifty, with a few outliers stretching beyond.

I added weekly gross to the model. Average ticket price. Run length. Eligibility year. The obvious confounds. The coefficient stayed positive. The effect was still there, although it shrank slightly. The p-value drifted up to around 0.09, which is the statistical equivalent of a shrug.

I started drafting the article in my head. The Tony Awards were not exactly rigged, but they were riggable. The path to victory was clear: assemble a coalition, expand the network, buy the influence. Not literally buy it, but buy access to it through the currency of above-the-title billing. Every co-producer gets their name on the poster and, more importantly, becomes eligible for the Tony Award if the show wins.

But eligibility does not translate into influence. The ability to accept a trophy and the ability to shape voter behavior are entirely different currencies. And I couldn’t contend with the thought that co-producers are generally either new to the business or have a laissez-faire approach to the industry’s inner workings (either deliberately or because of obscurity, as many of my other articles have touched on). These individuals surely lack substantial voting power, so why would it matter if there were more of them?

Perhaps, when producer count predicts anything, it does so as a proxy for scale, ambition, and GP capacity—not because the forty-seventh co-producer personally convinces anyone to vote.

I sat with this for a while. For the next two days, I wrote a draft of an article analyzing this and what it meant, sent it to a few people whose judgment I trust, closed my laptop and enjoyed two day-old Turkey.

The Mistake

Different day. Different crisis.

I was in the living room, sitting on the couch, doomscrolling while my dad was watching a YouTube video he discovered about using ChatGPT to diagnose and repair a Kia Sonata engine. He does not own a Kia Sonata. He has never owned a Kia Sonata. He has, to my knowledge, never opened the hood of any car for any reason other than to add windshield wiper fluid, and even that required a phone call for instructions. I digress.

In a moment, something compelled me to think about my dataset again, and the core criticism hit me: I had been treating Broadway as a single population when it is, in fact, four distinct ecosystems operating under entirely different laws.

Original Plays. Original Musicals. Play Revivals. Musical Revivals.

These are not variations on a theme. They are four different industries that happen to share the same awards ceremony.

When the realization hit, I stood up so fast I knocked over his tea. The mug went sideways. The tea went everywhere. The carpet, the couch, his phone.

I had to rerun everything by category.

From the living room, I could hear him still yelling. Something about the mess and how he just spent $200 on this rug. YouTube video was still playing. I did not care. I needed to see what the data looked like when I stopped averaging across four completely different games.

This is also, I suspect, not how normal people spend their Saturday mornings.

The Four Kingdoms

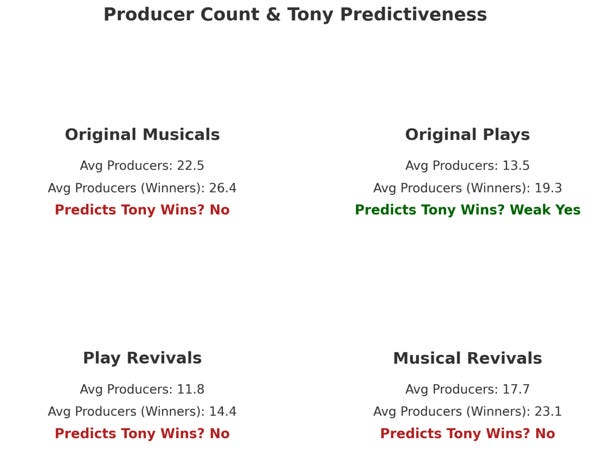

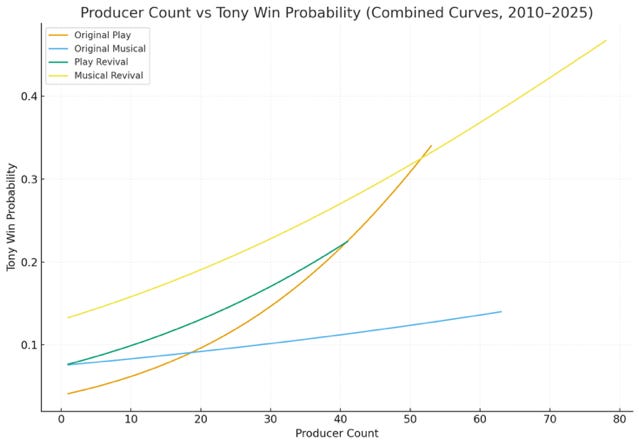

The aggregate picture was hiding the architecture. When I reran the regressions separately for Original Plays, Original Musicals, Play Revivals, and Musical Revivals—each with Tony win as the dependent variable and producer count, grosses, ticket price, and eligibility year as predictors—the entire structure shifted. Patterns that looked meaningful in the monolith dissolved, and the only detectable producer-count signal with any p-significance that mattered surfaced in Original Plays.

When I saw these curves laid out side by side, I felt something I can only describe as vertigo. I had walked in expecting to find a clear systemic advantage in favor of capital + network. I found instead four different games being played under the same roof, each with its own physics, and in three of the four games, producer count is effectively irrelevant.

Why Original Plays Might Be Different

I have been turning this over in my mind. Why would producer count predict success for original plays but not original musicals?

Perhaps it's because original plays enter the season without musical numbers, spectacle, or pre-sold IP to anchor voter perception? They are evaluated almost exclusively on individual interpretation—on the script, the performances, the direction, the room they create. Because the work is more variable in reception and more dependent on taste, voter opinion is far more elastic. Since the electorate lacks a shared reference point, the producers’ ability to shape narrative (what the show “means” and why it matters) carries disproportionate weight.

In other words, original plays live or die on story, and not just the one on stage. The framing around the work, the conversations the producers ignite, the alliances they form with voters and tastemakers, the coherence of the campaign’s message. A larger producing team may matter because it expands the show’s narrative surface area at the exact moment voters are deciding what the work is about.2

Original musicals tell the opposite story, and the reason, I believe, is saturation.

Everyone mounting an original musical on Broadway has massive campaign resources. Everyone has access to the same voter networks. Everyone is playing the same game at the same level of intensity. When the baseline is already maxed out, variation in producer count stops predicting anything. The signal drowns in noise.

The Individuality Problem

But saturation is only half the explanation. What I had overlooked, consequently, is the reality that Tony voters themselves are not a unified body. They fracture into constituencies with distinct incentives. Road presenters vote according to touring economics; a Tony win for an original musical dramatically improves its post-Broadway viability, while a win for a well-known IP barely alters their sales calculus. Actors, directors, and writers, by contrast, tend to reward work that embodies aesthetic ambition. Press agents and general managers may often gravitate toward projects that signal professional momentum or future employability. Theatre owners, producers, regional bookers, designers—each filter the same season through a different set of stakes.

There is, in other words, no singular “voter.” There are overlapping blocs whose priorities shift not just year to year, but category to category. In a landscape this heterogeneous, a variable as blunt as producer count could never reliably capture the dynamics at play.

Therefore, what distinguishes winners from losers in this kingdom is something else entirely. Quality, maybe. Cultural moment. The ineffable thing that made Hamilton feel inevitable and Paradise Square feel effortful. Whatever it is, my model cannot see it.

I found this oddly comforting. The data was telling me that in the most expensive, most competitive category on Broadway, the thing that matters most is the thing that cannot be bought.

Or the data was telling me that the buying is so universal it no longer differentiates. I am not sure which interpretation I prefer.

A Final Thought About Art and Fugazi

I used to watch the Tony Awards every year with my Bubbie and my mom. We would sit together, and she would tell me about the shows she had seen decades ago, and I would dream about standing on that stage someday. I do not watch anymore. Not for any particular reason. I just stopped caring.

I do not mean this as a pose. I mean it as a fact about my own psychology that surprises me. I used to fantasize about being an EGOT winner. I would rehearse acceptance speeches in the shower. Make space on my mantel for my soon-to-be awarded Oscar. Somewhere along the way, that fantasy lost its hold.

What I dream about now is different. I dream about what people will say when they leave my show. The conversations they will have on the subway home. The quiet moments when something I made surfaces in someone’s memory months later and they cannot quite explain why. That is what I want. That is what I have always wanted, underneath the prestige fantasy, and it took me a long time to realize the two things are not the same.

I went looking for evidence of a popularity contest, a system you could game by assembling the right coalition of investors. I found something else entirely. I found 831 individuals – not a monolith, but a diverse body with varying artistic tastes and commercial interest - who, despite their professional stakes, commercial interests and the possibility of internal voter bloc strategies are just voting for what they think is good.

Sure, economic success and average ticket prices are statistically significant predictors of winners in all categories. But economic success is itself a signal. The shows making serious money are often the ones that connected with audiences, captured something in the cultural moment, and worked. The causality is tangled, but the correlation suggests voters are responding to the same qualities that make shows commercially viable. They are voting for shows that matter.

This does not mean the Tony Awards are perfect. They are not. Prestige systems always favor certain types of work, certain types of voices, certain types of stories. But the data shows the outcomes are not predicted by network effects. They are not as riggable as my 25-year-old anti-establishment self wanted to believe. In the aggregate, voters really are just voting for what moves them.

But that does not change how I think about the whole thing. I do not want 831 voters to be the final arbiter of whether the art I make is good. I do not want any voters deciding that. But I also do not need to be cynical about their judgment. They are trying, within the constraints of their own taste and experience, to recognize excellence.

Art is not a democracy. It is not a competition. It is a conversation between the work and whoever encounters it, and that conversation happens in all four kingdoms, regardless of what anyone votes, regardless of what any model predicts.

So maybe the question is not whether more producers lead to more Tony wins. The answer to that question is: barely, and only sometimes, and not in the way anyone thinks. Maybe the question is whether the validation matters, and whether chasing it changes the work you are willing to make, and whether the variance you are trying to control is the variance that defines a life.

Make the work anyway. Make it strange and difficult and true. Make it for the people in the room, not the people counting ballots. Make it knowing that the 831 voters are probably going to vote for what they think is good, which means the only real strategy is to make something good. Make it knowing that even if you win, the award is not the thing.

The statuettes are about $3,000 each if you want to buy one. I hear they look nice on a shelf, or even in a LinkedIn bio.

But the work, the real work, does not require a consensus. It never did. Not even if you spill your father’s tea while he is learning how to fix a car he does not own.

The dataset I built for this analysis aggregates every Broadway production eligible for Tony consideration between the 2009–10 and 2024–25 seasons, assigning each show to an eligibility year rather than a calendar year. I harmonized producing credits by collapsing variations in above-the-title listings into a unified producer count (each link counted as one entity - so for example, Marsha Holder/John Liebowitz (fictitious names) counted as one entity. I then merged those figures with weekly gross revenue, average ticket price, and run-length data. Shows were further stratified into four categories—Original Play, Original Musical, Play Revival, Musical Revival. Eligibility year was added as a temporal control to correct for industry-wide shifts in financing and award dynamics over the fifteen-year period.

I must note, the model said the effect was statistically significant, which is not the same as saying the effect is causal. This is a distinction I wish more people understood, including, on some days, myself.